Over the last year, I was involved in a side project on aneuploidy and cancer. It had started as a pretty vague idea which, as we added more and more details and references to this idea over the year, has grown to a testable hypothesis. In our little Gedankenexperiment we asked, what would happen if X, Y and Z were true and found a beautiful tentative answer. For all authors, this was a side project to their main lines of research, so we are curious to learn if and how the research community will pick up on this idea:

Johannes Engelken, Matthias Altmeyer, Renty Franklin. 2014. The disruption of trace element homeostasis due to aneuploidy as a unifying theme in the etiology of cancer. http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2014/03/14/002105

During discussions, a few questions have come up, that we try to clarify in this FAQ (frequently asked questions) post.

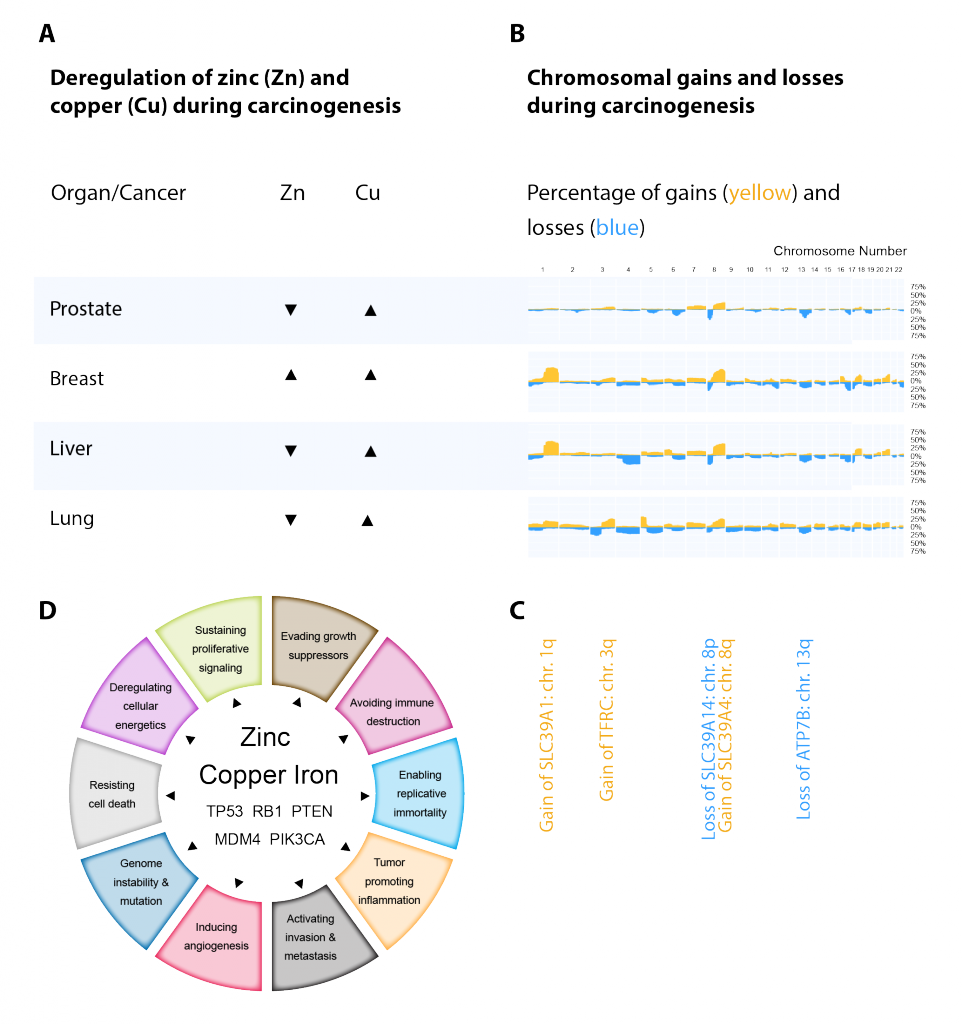

Figure 1: Aneuploidy Metal Transporter Cancer (AMTC) Hypothesis. (A) Deregulated trace element concentrations in different tumors, typically lower zinc and higher copper when compared to normal tissue. (B) Recurrent chromosomal gains leading to a high percentage of tumor samples with three copies of a particular chromosome arm (orange) or losses (one copy, blue) across many samples are visualized (http://progenetix.org). Based on (A) previous evidence of deregulated trace element concentrations and (B) characteristic chromosomal gains and losses (aneuploidy) in diverse types of cancer, we hypothesize that there may be a causal link between these two observations, i.e. (C) gains and losses of specific chromosome arms that include metal transporters may lead to the disruption of trace element homeostasis during carcinogenesis, which in turn might contribute to cancer progression. (D) The disruption of trace element homeostasis likely affects several of the established hallmarks of cancer and hereby, together with established recurrently mutated cancer genes, may contribute to malignant transformation. If this hypothesis were to be confirmed, the disruption of trace element homeostasis would emerge as a unifying theme in cancer research.

Abstract for Adults (Non-Scientists): One hundred years ago, it was suggested that cancer is a disease of the chromosomes, based on the observations that whole chromosomes or chromosome arms are missing or duplicated in the genomes of cells in a tumor. This phenomenon is called “aneuploidy” and is observed in most types of cancer, including breast, lung, prostate, brain and other cancers. However, it is not clear which genes could be responsible for this observation or if this phenomenon is only a side effect of cancer without importance, so it is important to find out. A second observation from basic research is that concentrations of several micronutrients, especially of the trace elements zinc, copper and iron are changed in tumor cells. In this article, we speculate that aneuploidy is the reason for these changes and that together, these two phenomena are responsible for some of the famous hallmarks or characteristics that are known from cancer cells: fast growth, escape from destruction by the immune system and poor DNA repair. This idea is new and has not been tested yet. We name it the “aneuploidy metal transporter cancer” (AMTC) hypothesis. To test our idea we used a wealth of information that was shared by international projects such as the Human Genome Project or the Cancer Genome Atlas Project. Indeed, we find that many zinc, iron and copper transporter genes in the genome are affected by aneuploidy. While a healthy cell has two copies of each gene, some tumor cells have only one or three copies of these genes. Furthermore, the amounts of protein and the activities of these metal transporters seem to correlate with these gene copy numbers, at least we see that the intermediate molecules and protein precursors called messenger RNA correlate well. Hence, we found that the public data is compatible with our suggested link between metal transporters and cancer. Furthermore, we identified hundreds of studies on zinc biology, evolutionary biology, genome and cancer research that also seem compatible. For example, cancer risk increases in the elderly population as well as in obese people, it also increases after certain bacterial or viral infections and through alcohol consumption. Consistent with the AMTC hypothesis and in particular, the idea that external changes in zinc concentrations in an organ or tissue may kick off the earliest steps of tumor development, all of these risk factors have been correlated with changes in zinc or other trace elements. However, since additional experiments to test the AMTC hypothesis have not yet been performed, direct evidence for our hypothesis is still missing. We hope, however, that our idea will promote further research with the goal to better understand cancer – as a first step towards its prevention and the development of improved anti-cancer therapies in the future.

Abstract for Kids: We humans are made up of many very small building blocks, which are called cells. These cells can be seen with a microscope and they know how to grow and what to do from the information on the DNA of their chromosomes. Sometimes, if this information is messed up, a cell can go crazy and start to grow without control, even in places of the body where it should not. This process is called cancer, a terrible disease that makes people very sick. Scientists do not understand exactly what causes cells to go crazy, so it would be good to find out. Many years ago, scientists observed that chromosomes in these cancer cells are missing or doubled but could not find an explanation for it. More recently, scientists have detected that precious metals to our bodies, which are not gold and silver, but zinc, iron and copper, are not found in the right amounts in these crazy cancer cells. There seems to be not enough zinc and iron but too much copper, and again, scientists do not really understand why. So there are many unanswered questions about these crazy cancer cells and in this article, we describe a pretty simple idea on how chromosome numbers and the metals might be connected: we think that the missing or doubled chromosomes produce less or more transporters of zinc, iron and copper. As a result, cancer cells end up with little zinc and too much copper and these changes contribute to their out-of-control growth. If this idea were true, many people would be excited about it. But first this idea needs to be investigated more deeply in the laboratory, on the computer and in the hospitals. Therefore, we put it out on the internet so that other people can also think about and work on our idea. Now there are plenty of ways to do exciting experiments and with the results, we will hopefully understand much better why cancer cells go crazy and how doctors could improve their therapies to help patients in the future.

Disclaimer